Immersive Tools: Large-Scale Physical Models and the Search for Kairotic Time

Kevin Barden, Rivers Barden Architects

Ross Wienert, University of Houston / CONTENT Architecture

The Speed of Forgetting

In the summer of 2022, the introduction of the generative text-to-image artificial intelligence (AI) programs Midjourney and Stable Diffusion forever altered the practice of design. For the first time, a user could submit text prompts to a program and receive a set of images that provide an interpretation of a particular mood, feeling, and atmosphere within a matter of seconds. Across disciplines in design practice and education, the presence of these programs has since opened new realms of conceptual image creation. As showcased in the Chat GPT generated article published in the Architizer AI Journal, “an architectural visualization of a sleek urban loft in the heart of a bustling city at night,” or “a visual masterpiece of a modern courtyard residence with lush landscaping and a tranquil pool,”1 require little more than the click of a button.

While there is a certain seductiveness to these images, many scholars and practitioners at the forefront of generative AI image technology have come to a similar consensus that this tool is not an end in itself. In a recent episode of the podcast, The Second Studio, Andrew Kudless, the founder of Matsys and the Bill Kendall Memorial Endowed Professor at the University of Houston’s Hines College of Architecture and Design, discusses a similar notion that, “just because you can make a beautiful image [using artificial intelligence] doesn’t mean that it’s architecture”2. In other words, the role these AI generated images play in the design process does not negate the need for asking deep questions through alternative methods of exploration, discovery, and iteration for a design to realize its full potential. If anything, the presence of this new tool may heighten the need to renew emphasis on processes that explore the physical, experiential, and tactile qualities of design.

Precisely at a time when the use of AI generated images might be the trend within current learning environments, the timelessness of exploring conditions of space, light, and material qualities through the making of large-scale physical models provides a foundational experience necessary for students to engage with a deeper level of comprehension before entering the field of design. In the face of radical advances in image generating technology, the large-scale physical model has re-emerged as a design tool that enables students (and experienced practitioners) to explore, comprehend, and communicate the experiential dimensions of architecture as well as provide an immersive learning experience essential for the development of a student’s creative voice, sense of discovery, and long-term learning.

Chronos and Kairos

“For what is time? Who can easily and briefly explain it?”3. Saint Augustine of Hippo poses these questions to himself and the reader in his collection of ruminations entitled, Confessions. In his writing on ‘time’, his observations peer deep into our relationship with an entity that confronts everyone and everything on a daily basis, however, when searching for a definition, elusiveness strikes. In his search, Augustine turns toward an understanding that perhaps time exists within us, proclaiming “It is in you, O mind of mine, that I measure the periods of time”4, before exploring the cyclical nature of past, present, and future. Further yet, the notion exists that perhaps the conception of time is eternal and something we will simply never fully comprehend.

One response to Augustine’s initial questions stems from the classical understanding of time derived from the two Greek words chronos and kairos. Succinctly defined, “chronos expresses the fundamental conception of time as measure, the quantity of duration, the length of periodicity, the age of an object or artifact, and the rate of acceleration as applied to the movements of identifiable bodies”5. In the context of everyday life, this understanding of time provides a framework for keeping schedules and making appointments, the arrivals and departures of public transportation, as well as the celebration of birthdays and anniversaries, to name a few. Kairos on the other hand, “points to a qualitative character of time, to the special position an event or action occupies in a series, to a season when something appropriately happens that cannot happen at ‘any’ time, but only at ‘that time’”6. With kairos, questions arise as to what is the ‘right time’ for an activity or event to occur. Again, in the context of everyday life, this could be thought of as the time for exploring a new research interest or going back to school for an advanced degree.

Both chronos and kairos possess distinct relationships with the work we produce, make, and create. One example of this can be found in the game of basketball where the quantitative presence of chronos provides a framework for the start and stop of each half, the ticking twenty-four second shot clock with each team’s possession, and the ever-present march of the game clock toward the finality of the contest. On the other hand, the qualitative presence of kairos can be felt by an individual player (or sometimes a group of players) when they reach a state of mind known as flow; in which there occurs an “alteration of the concept of time, [where] hours can pass in minutes and minutes can look like hours”7. The conditions of the game in this context combine in a specific way where the game slows down for the player. With all distractions having been removed the player is entirely present in the act of play where maximum enjoyment and creativity can be realized.

Another example of this distinction between chronos and kairos can occur when someone plays music, either individually or in a group. While chronos might set the stage for a band to perform a concert together at a specific time and location, the presence of kairos is responsible for the mindset of the musician and all the qualitative communication of specific timings between the person, their instrument, and other musicians. Similar to the example of the basketball game, it is precisely in these moments of kairotic time that enjoyment and creativity fully blossom for the individual and the group within the context of making and creating. In both cases, the participants feel so engaged and immersed in the act of creation and production associated with kairotic time that their sense of chronos erodes and fades away. They lose track of time and become immersed in the act.

Kairotic Space

Expanding on the previous definition given of kairos, Cynthia Miecznikowski Sheard shares, “Kairos is the ancient term for the sum total of ‘contexts,’ both spatial and temporal” and that, “[it] encompasses the occasion itself, the historical circumstances that brought it about, the generic conventions of the form, … [and] provides a method for deciding courses of action, and for deriving probable truths in a relativistic world ‘in which for every issue there are reasonable, contradictory positions”8. What is particularly interesting in this line of investigation, is the idea that a kairotic understanding of time presupposes a set of kairotic spatial qualities and relationships that allow for a deeper awareness of learning, exploring, and being in the world. Questions immediately arise as to what constitutes these spatial conditions. How can the spaces we inhabit allow for kairos and a mindset of flow in the creative process?

In writing about the presence of disability in academic spaces, Margaret Price offers, “Kairotic spaces are the less formal, often unnoticed, areas of academe where knowledge is produced and power is exchanged” and defines a kairotic space, “as one characterized by all or most of these criteria:

1. Events are synchronous; that is, they unfold in ‘real time’

2. Impromptu communication is required or encouraged.

3. Participants are tele/present.

4. The situation involves a strong social element.

5. Stakes are high”9.

Referencing back to the previous examples given of a basketball game and a group of musicians playing on a stage, one can argue that all five of these criteria are present. Distractions are fully removed, and participants are allowed to ‘lose themselves’10 in the active engagement of creative activity. As Daniel Stern notes, “[Kairos] is the coming into being of a new state of things, and it happens in a moment of awareness. It has its own boundaries and escapes or transcends the passage of linear time…It is a subjective parenthesis set off from chronos”11.

These conditions of kairotic space and time can be found in the optimal studio settings of architecture offices and academic programs. The Finnish architect Alvar Aalto gives a glimpse of this in his essay The Trout and the Stream, confiding with reader:

“When I personally have to solve some architectural problem, I am constantly –indeed, almost without exception – faced with an obstacle difficult to surmount, a kind of ‘three in the morning feeling’. The reason seems to be the complicated, heavy burden resulting from the way that architectural design operates with countless, often mutually discordant elements. Social, humanitarian, economic, and technological requirements combined with psychological problems affecting both the individual and the group, the movements and internal friction of both crowds of people and individuals – all this builds up into a tangled web that cannot be straightened out rationally or mechanically. The sheer number of various demands and problems forms a barrier that makes it hard for the basic architectural idea to emerge. This is what I do – sometimes quite instinctively – in such cases. I forget the whole maze of problems for a while, as soon as the feel of the assignment and the innumerable demands it involves have sunk into my subconscious. I then move on to a method of working that is very much like abstract art. I simply draw by instinct, not architectural syntheses, but what are sometimes quite childlike compositions, and in this way, on an abstract basis, the main idea gradually takes shape, a kind of universal substance that helps me to bring the numerous contradictory components into harmony”12.

Here we see the concerted effort of Aalto to remove outside distractions and become absorbed in a state of kairotic time and space. To “draw by instinct” he engages in a mindset akin to a state of flow to unlock the creative potential needed to meet the moment of the architectural problem. These kairotic moments provide optimal conditions for deep learning and the realization of ideas to take place. Notice though, that Aalto allows himself to surrender to this state only after “the feel of the assignment and the innumerable demands it involves have sunk into [his] subconscious.” In other words, only after an understanding of the “sum total of ‘contexts’” is gained can the conditions be set for physical, mindful, and intuitive explorations to take place.

The conditions of kairotic time and space are precisely what is needed for the creation of large-scale physical objects in the academic and professional studio setting. The search for these environments is often what draws one to work late into the night with a group of trusted colleagues where impromptu communication, presence, and the experience of ‘time’ allows for a state of flow to be reached without distractions. As Tod Williams and Billie Tsien share with us about their studio environment,

“Everyone knows what is going on around them. If there is a problem, it is shared, and of course we try to share the joys as well. The sense of well-being in the studio must be supported and nurtured by each member … Our office works not as an efficient machine, but as a loose and independent and somewhat inefficient family. The slowness of method allows us breath and breadth”13.

Kairotic Practice

Turning directly toward the use of large-scale physical models in the design process of architectural offices, we see the spatial and temporal presence of kairos specifically in the work of the Finnish-American architect Eero Saarinen (1910-1961) and the Swiss architect Peter Zumthor (1943-present). As Richard Knight notes,

“In the late 1950s, Saarinen upended the architectural profession and revolutionized the way buildings were designed by using large models to investigate the forms and functions of his intended work. Not since the Renaissance were models used as extensively as in Saarinen’s designs”14.

Prior to this, architectural designs were typically explored through the creation of orthographic plans, elevations, sections, and perhaps at the very end, a presentation model to communicate the project to the client. For Saarinen and his team, this radical shift in the design process provided a new way of exploring ideas by allowing a direct experiential connection to what was being designed. As relayed by Knight, who worked in Saarinen’s office, “drawings can fool both the client and the architect, who is intent on executing a beautiful drawing, when the challenge is to produce a beautiful building”15.

While Saarinen practiced at a time before the use of computer-aided drafting (CAD), Zumthor continues to practice at the peak of computer building information modeling (BIM), photorealistic digital renderings, and AI generated images. Both architects had access to various methods and techniques throughout the design process, however, each had a conviction that the deep learning necessary to explore qualities of space, light, and material can best be discovered through the making of large-scale physical models. In Thinking Architecture, Zumthor shares,

“All design work starts from the premise of this physical, objective, sensuousness of architecture, of its materials. To experience architecture in a concrete way means to touch, see, hear, and smell it. To discover and consciously work with these qualities – these are the themes of our teaching. All the design work in the studio is done with materials. It always aims directly at concrete things, objects, installations made of real material (clay, stone, copper, steel, felt, cloth, wood, plaster, brick)”16.

Not So Precious

Identifying the presence of kairos in the iterative design process of Saarinen’s and Zumthor’s architectural offices can best be illustrated through specific examples. For Saarinen, “his use of large three-dimensional studies literally took off when the office designed the TWA passenger terminal at Kennedy International Airport. From then on substantial models with changeable capabilities became part of the process”17. Completed in 1962, the TWA Flight Center is “a significant example of mid- twentieth-century modern architecture, engineering, and airline terminal planning. A masterpiece of expressionist architecture, it was designed … as a direct rebuttal to the abstracted rectilinear forms of the International Style which dominated corporate American architecture in the 1950s”18. Largely defined by a soaring curvilinear thin-shell concrete roof and four Y-shaped piers, the building seems to defy gravity akin to the flight of the airplanes the building serves. In the office, the design process for the TWA Flight Center focused on the use of physical models to make design decisions where the scale of the models was often large enough for a person to occupy while working on them. Images of both rough study models as well as highly refined presentation models exist for this project. The presence of the former provides evidence that the office treated these models as tools for exploring ideas. Knight shares:

“Everyone worked with models. Jokingly, the fledglings were referred to as cardboard cutters. I enjoyed working with study models, it was dynamic, I discovered relationships that drawings never revealed, and it gave me a feeling of accomplishment. Eero’s models, although sizable, were made of modest paper products, occasionally reinforced with wood. These creations appeared unpretentious, no matter how much energy had gone into them, for they were humble works-in-progress, subject to change. They were mostly monochromatic, emphasizing form and the effects of shading”19.

In this first-hand account, we begin to see the presence of kairotic spatial and temporal conditions. Referring back to the criteria outlined by Margaret Price for kairotic space: the stakes are high in designing an international airport terminal, there exists a strong social element between the team of present participants, and a sense of impromptu communication exists with the physical models constructed of modest materials and subject to change at any time. This passage also highlights that the types of ‘events’ which occur in this design process structured around kairos can simply be a series of meaningful design decisions that were not previously apparent. Furthermore, with the physical models in a constant state of change, it is easy to infer the iterative process of exploration in the office. Later in Knight’s writing, he shares that “none know better than the staff of Eero’s exhaustive, often dogged pursuit of excellence. He was amused when we suggested identifying his design alternatives in random order, schemes F, M, Q rather than A, B, C, to imply an even greater exploration of possibilities”20.

This same dedication to making design decisions through experiential physical models occurs in Peter Zumthor’s office. While Saarinen was particularly interested in exploring the experiential qualities of space and light, Zumthor adds the dimension of materiality to his investigations. An example of this can be found in the design process for the Thermal Baths located in Vals, Switzerland. As described by Zumthor,

“Stone and water: a love affair. At some point in the design process it was no longer difficult to grasp these two primary materials as mutually invigorating energies, and to trust that with this pair of elements we could create and express almost everything that our thermal spa in the mountains seemed to require”21.

Constructed from Valser quartzite, a local stone, the thermal spa contains a grouping of six baths within a meandering jungle of stone pillars built into the side of the mountain. Throughout the design process,

“Sensuous images of the physical experience of stone and water and light, translated into geometry and space and construction, inspired our work. The design from inside to outside was central to the concept. We dreamed of a kaleidoscope of room sequences, affording ever new experiences – to the ambling, curious, astonished, or surprised visitor. Like walking in a forest without a path. A feeling of freedom and pleasure”22.

This process of working from inside to outside, requires an inversion of how architects typically make decisions early in the design process. Rather than focusing on a particular formal configuration of how a building might appear from the exterior, working from the inside out immediately prioritizes the immersive sensory qualities of space, light, and material. In a publication dedicated to the process and ethos of the project, Zumthor describes the physical models that were utilized in the design process,

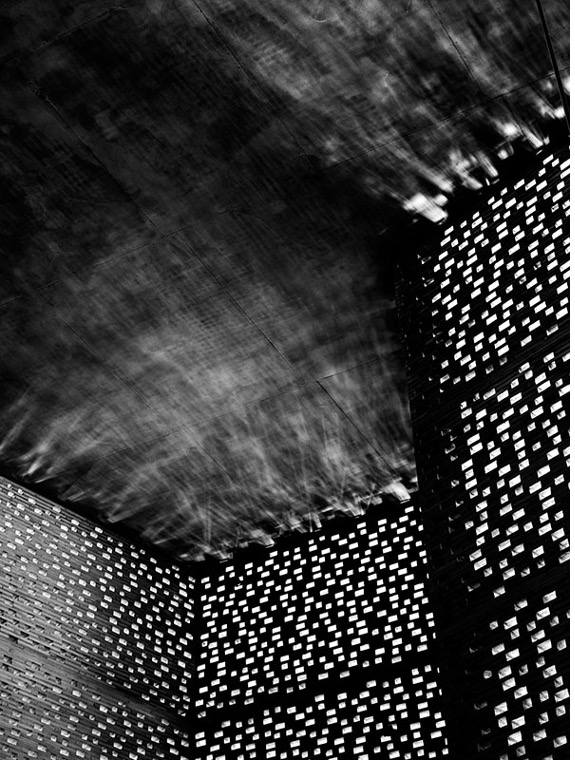

“Using large outdoor models, we studied ways in which the combination of daylight, coming in through the joints in the roof, and the water below could create a specific atmosphere in the rooms; we wanted to learn how to stage the effects in a meaningful way. And because we imagined that the air in the shadowy mass of meandering hollows in the baths would always be humid and the floors of stone would always be wet, we built our models out of stone or out of aerated concrete and filled them with water in order to observe the effects created by daylight under those conditions: stone and water, shadow and light”23.

Resonating with concepts of kairotic time and space, Zumthor and his team constructed these large-scale models to test and learn about the qualities of the spatial conditions being designed. These models offer a tool that aids in the rigorous search for design decisions that feel ‘appropriate’ and ‘right’ given the context of the project.

Change in Perspective

Typically, the abstract study models used in academic and professional architectural settings exist at a scale small enough that they fit within the palm of your hand. As a result, they best demonstrate exterior qualities, rendering the building as a formal object viewed from a distance. While that small scale aids in maintaining a level of abstraction and legibility, it also limits the capacity of those models to speak to the interior qualities one would experience upon entering the building.

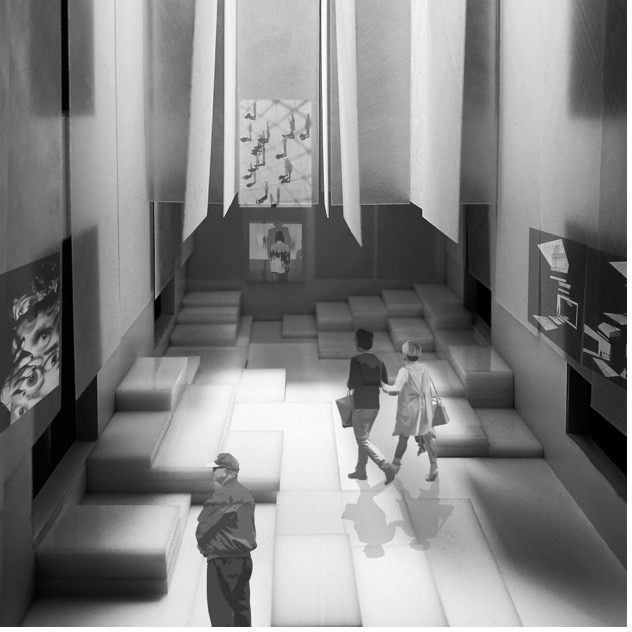

Addressing those questions of the interior requires a radical re-consideration of the scale of the model and how it is viewed. Rather than something handheld and viewed from a distance, the large-scale physical models must be large enough that you can fit your head inside (or at least a small camera). From this vantage point, the rules of perspective come into play. Horizon lines and vanishing points emerge, and the model begins to reflect the conditions of the building it represents. This method of designing through the making of physical models is captured in Peter Zumthor’s statement that, “There are no cardboard models. Actually, no ‘models’ at all in a conventional sense, but concrete objects, three-dimensional works on a specific scale”24. The model becomes analogous to reality in terms of how we experience spatial relationships, how materials offer textural qualities, and how the way that light enters animates spaces in unique and changing ways.

The capacity of the large-scale physical model to reflect the reality of the building’s experiential qualities offers a compelling tool with which to study and understand architectural precedents, especially in the academic studio setting. Typically, these precedent studies ask students to research a building, produce drawings, and construct small conceptual or massing models of the building they investigate. Under those conditions, their understanding of the building’s interior remains relatively limited to the handful of photographs curated and published by the architect upon the project’s completion. These images only capture the interior at a specific moment in time. While they show what light does at that moment, they fail to demonstrate how lighting conditions change throughout the course of the day.

In addition to providing a sense of construction and assembly, the large-scale physical model offers students a “concrete object” that mimics the way light changes within the interior of the precedent. For each precedent, students identify a moment within the space where light plays a critical role in the experience of the building and construct a model large enough to capture that moment. Upon completion, students can observe how light enters and changes throughout the course of the day by taking that model outside into the daylight and orienting it to correspond to the actual building, or by replicating the path of the sun using a spotlight. In either case, students place cameras within the model to record lighting conditions through photographs and videos that communicate how lighting conditions change within. This exercise provides students with a deeper understanding of the relationship between the openings in the skin of the building and the atmospheres they create within it. The lessons learned from the precedent studies inform the student’s decisions as they engage in their own design project.

The “concrete object” of the precedent offers students the opportunity to explore the potential of large-scale physical models with a design that already exists and provides an example of how the tool works before utilizing that tool to shape their own designs. This practice opens their eyes to design opportunities that exist when working at an expanded scale. Questions of space, material assemblies, textures, and the way that light interacts with a surface all gain a sense of presence when the model increases to a scale that allows immersion to take place.

One issue educators potentially encounter with today’s students springs from the relatively long amount of time these models take to construct in comparison to the rapid progression that more and more advanced digital tools enable. At a moment in architectural education where Artificial Intelligence offers visually striking results almost instantaneously, the value of the physical model and the time that must be invested to bring it to fruition becomes easy to question. Although the time required to design, construct, and explore ideas via the physical model are immense, the practice of physically modeling enables a deeper learning experience.

While the equation isn’t quite scientific, Milan Kundera’s suggestion that “the degree of slowness is directly proportional to the intensity of memory; the degree of speed is directly proportional to the intensity of forgetting”25 feels like an accurate assessment of the relationship between time invested and depth of learning. That deeper level of learning exists if the students immerse themselves in the iterative process of making. Faculty possess the responsibility for enabling these deeper learning experiences as much as the students.

When leading these exercises, instructors must exercise patience and recognize that these are long-term exercises that require time to investigate and explore thoroughly. For students to work with these tools and explore their designs with a sense of kairos, faculty must provide a structure to manage the aspects of chronos that allows the work to take place. If faculty afford students the time to engage in a “patient search”26 for possibilities, students are more likely to immerse themselves in deeper investigations that provide long-term learning.

Kairotic Time in the Studio

In the fall semester of 2024, each second-year design studio at the University of Houston College of Architecture and Design engaged in the practice of constructing large-scale physical models as part of an adaptive re-use project. At the outset of the semester, the faculty and program director notified students that after their mid-reviews took place they would model their designs at a scale of ½”=1’-0”, setting the stage and expectations for these tools early on. While the students constructed models that were quite large, the project was broken into smaller more manageable steps that helped to make the work less daunting. Internal deadlines were established, small prototypes were constructed before taking on the full model, and more time was allotted when it became clear that none of the studios would be able to complete their models effectively in the time initially provided. Faculty encouraged students to work with a sense of rigor while also empathizing with the challenges students encountered.

This project took place amid a desire from faculty to rebuild a studio culture that faltered during the pandemic and did not return with the same vigor after students returned to attending studios in-person. With a curriculum that had become increasingly reliant on digital tools, students felt content to work alone from their own homes, rather than collaboratively in the studio. This issue was partially addressed by a renewed emphasis on physical fabrication with this cohort in their first year, but with the small scale of the artifacts they made, many students were still working outside of the studio.

The large-scale physical models that students constructed at the end of the semester ranged in size, but most of them were roughly 2’ wide, 3’ long, and 2’ high, making them too cumbersome to transport easily. As a result, the students felt compelled to assemble these models in the studio and keep them there, which required most of the students to work collaboratively in the same space.

While the faculty did not seek out Margaret Price’s criteria for a kairotic space explicitly, all the necessary parts were present. The ability to be there together in person as the models were built, communicate with each other regarding questions, and converse with friends while working on a design that each cared deeply about developing, resulted in an enlivened studio atmosphere that had been rare in recent years. There is hope that the positive experience this exercise provided exposed this cohort of students to the benefits of working together in the studio and that they will continue to do so in the future, regardless of the scale of their models.

The Slowness of Memory

While a professional in an office must address the very real relationship between time and money, the academic setting of the design studio remains somewhat insulated from those pressures in the name of education. Although it may be unlikely that students will be offered the opportunity to invest a large amount of time in large-scale physical models when they reach the profession, a belief exists that the extended time invested in these exercises as a student result in a deeper sense of learning and a greater understanding of the quality of the spaces designed in the office setting. Even if their tools for design exploration change in the future, the lessons students learn in these exercises will continue to inform their design decisions. When the task at hand calls for the expediency that the digital realm enables, hopefully students will recall and apply the lessons learned from the immersive nature of the physical realm.

References

Aalto, Alvar. In His Own Words. Edited by Göran Schildt. Helsinki, Finland: Otava Printing Works, 1997.

Architizer AI. “AI Architecture: 15 Breathtaking Modern Residences (Prompts Included).” Architizer, (2024). Retrieved May 13, 2024 from https://architizer.com/blog/inspiration/collections/ai-architecture-15-breathtaking-modern-residences-prompts-included/

Bourderonnet, Maria, and David Bruce Lee, “#351 – Andrew Kudless, Founder of Matsys on A.I. in Architecture.” The Second Studio, (1988). Retrieved May 13, 2024 from https://www.secondstudiopod.com/podcasts-13/351-andrew-kudless-founder-of-matsys-on-ai-in-architecture

Carter, Michael. “Stasis and Kairos: Principles of Social Construction in Classical Rhetoric.” Rhetoric Review 7, no. 1 (1988): 97-112. https://www.jstor.org/stable/465537

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York, NY: Harper Perennial, 1990.

Historic American Buildings Survey, Creator, Eero Saarinen, Ammann & Whitney, Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo And Associates, Sponsor Port Authority Of New York And New Jersey, Richard W Southwick, Maya Foty, et al., Brandt, Peter, photographer. 1933. Trans World Airlines Flight Center, John F. Kennedy International Airport, Jamaica Bay, Queens subdivision, Queens County, NY. Queens County New York Subdivision Queens, 1933. Documentation Compiled After. https://www.loc.gov/item/ny2019/.

Knight, Richard. Saarinen’s Quest: A Memoir. San Francisco, CA: William Stout Publishers, 2008.

Milan Kundera. Slowness. New York, NY: Harper Perennial, 1996.

Le Corbusier. Creation Is a Patient Search. Translated by James Palmes. Introduction by Maurice Jardot. New York: Praeger, 1960.

Mardell, Ben, Jen Ryan, Mara Krechevsky, Megina Baker, Savhannah Schulz, and Yvonne Liu-Constant. A pedagogy of play: Supporting playful learning in classrooms and schools. Cambridge, MA: Project Zero, 2023.

Price, Margaret. Mad at School. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2011.

Saint Augustine of Hippo. Confessions. Translated by Albert C. Outler. Louisville, KY: Westminster Press, 1955.

Sheard, Cynthia M. “Kairos and Kenneth Burke’s Psychology of Political and Social Communication.” College English 55, no. 3 (1993): 291-310. https://doi.org/10.2307/378742

Smith, John E. “Time, Times, and the ‘Right Time’; ‘Chronos’ and ‘Kairos’.” The Monist 53, no. 1 (1969): 1-13. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27902109

Stern, Daniel N. The Present Moment in Psychotherapy and Everyday Life. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2004.

Williams, Tod, Billie Tsien. “Works.” 2G International Architecture Review 9, no. 1 (1999): 130-137.

Zumthor, Peter. Thinking Architecture. Basel, Switzerland: Birkhäuser, 2005.

Zumthor, Peter. Peter Zumthor Therme Vals. Zürich: Scheidegger & Spiess, 2007.

Zumthor, Peter. Peter Zumthor 1985-2013: Vol. 2. Zürich: Scheidegger & Spiess, 2014.

Footnotes

- Architizer AI. “AI Architecture: 15 Breathtaking Modern Residences (Prompts Included).” Architizer, 2024, Retrieved May 13, 2024, https://architizer.com/blog/inspiration/collections/ai-architecture-15-breathtaking-modern-residences-prompts-included/ ↩︎

- Maria Bourderonnet and David Bruce Lee. “#351 – Andrew Kudless, Founder of Matsys on A.I. in Architecture.” The Second Studio, 2023, Retrieved May 13, 2024 from https://www.secondstudiopod.com/podcasts-13/351-andrew-kudless-founder-of-matsys-on-ai-in-architecture ↩︎

- Saint Augustine of Hippo. Confessions, Translated by Albert C. Outler (Louisville, KY: Westminster Press, 1955), Chapter XIV, 17. ↩︎

- Ibid, Chapter XXVII, 36. ↩︎

- John E. Smith, “Time, Times, and the ‘Right Time’; ‘Chronos’ and ‘Kairos’.” The Monist 53, no. 1 (1969): 1. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27902109 ↩︎

- Ibid, 1-2. ↩︎

- Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience (New York, NY: Harper Perennial, 1990), 3. ↩︎

- Cynthia M. Sheard, “Kairos and Kenneth Burke’s Psychology of Political and Social Communication.” College English, 55 no. 3 (1993): 291. https://doi.org/10.2307/378742 ↩︎

- Margaret Price, Mad at School (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2011), 155-156. ↩︎

- Ben Mardell, Jen Ryan, Mara Krechevsky, Megina Baker, Savhannah Schulz, and Yvonne Liu-Constant, A pedagogy of play: Supporting playful learning in classrooms and schools (Cambridge, MA: Project Zero, 2023), 17. ↩︎

- Daniel N. Stern, The Present Moment in Psychotherapy and Everyday Life (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 2004). ↩︎

- Alvar Aalto, In His Own Words, Edited by Göran Schildt. (Helsinki, Finland: Otava Printing Works, 1997), 108. ↩︎

- Tod Williams and Billie Tsien, “Works.” 2G International Architecture Review, 9 no. 1 (1999): 134. ↩︎

- Richard Knight, Saarinen’s Quest: A Memoir (San Francisco, CA: William Stout Publishers, 2008), 21. ↩︎

- Ibid, 22. ↩︎

- Peter Zumthor, Thinking Architecture (Basel, Switzerland: Birkhäuser, 1999), 66. ↩︎

- Richard Knight, Saarinen’s Quest: A Memoir (San Francisco, CA: William Stout Publishers, 2008), 22. ↩︎

- Historic American Buildings Survey, Creator, Eero Saarinen, Ammann & Whitney, Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo And Associates, Sponsor Port Authority Of New York And New Jersey, Richard W Southwick, Maya Foty, et al., Brandt, Peter, photographer. Trans World Airlines Flight Center, John F. Kennedy International Airport, Jamaica Bay, Queens subdivision, Queens County, NY. Queens County New York Subdivision Queens, 1933. Documentation Compiled After. https://www.loc.gov/item/ny2019/. ↩︎

- Richard Knight, Saarinen’s Quest: A Memoir (San Francisco, CA: William Stout Publishers, 2008), 24. ↩︎

- Ibid, 35. ↩︎

- Peter Zumthor, Peter Zumthor 1985-2013: Vol. 2 (Zürich: Scheidegger & Spiess, 2014), 39. ↩︎

- Ibid, 40. ↩︎

- Peter Zumthor, Peter Zumthor Therme Vals. (Zürich: Scheidegger & Spiess, 2007), 70. ↩︎

- Peter Zumthor, Thinking Architecture (Basel, Switzerland: Birkhäuser, 2005), 66. ↩︎

- Milan Kundera, Slowness (New York, NY: Harper Perennial, 1996). ↩︎

- Le Corbusier. Creation Is a Patient Search. Translated by James Palmes. Introduction by Maurice Jardot. New York: Praeger, 1960). ↩︎

Explore

Timbergrove Renovation

Houston, Texas

Residential

In Houston’s Timbergrove neighborhood, this renovation transforms a traditional layout into an open, light-filled home designed for entertaining. Walls between kitchen, living, and dining areas were removed to create seamless flow, with custom millwork adding warmth, storage, and subtle definition to each space.

David Cedeño

Bartender & Artist

Food and Beverage

In this episode our resident architects Joe Rivers and Kevin Barden visit with David Cedeño, a bartender from Houston, Texas. Bartender David Cedeño has seen it all during the last two decades in the service industry, from basic mixed drinks, to the wine bar craze, to craft beer and the more recent mixology trend. Listening to David talk about his profession, it's clear that to him, crafting cocktails is more of an art form than anything else. Joe and Kevin visit with David about the job of a bartender, the importance of composition, his experience as a painter, and his message for creative types with a passion.

Principal Spotlight: Joe Rivers

Joe Rivers

Writing

Meet one of our Principals, Joe Rivers! Joe approaches architecture from the bottom up, and is an expert negotiator between details, constructibility and the larger vision of each project. He enjoys cooking and canoeing in his spare time.